Attachment Theory

What is Attachment Theory?

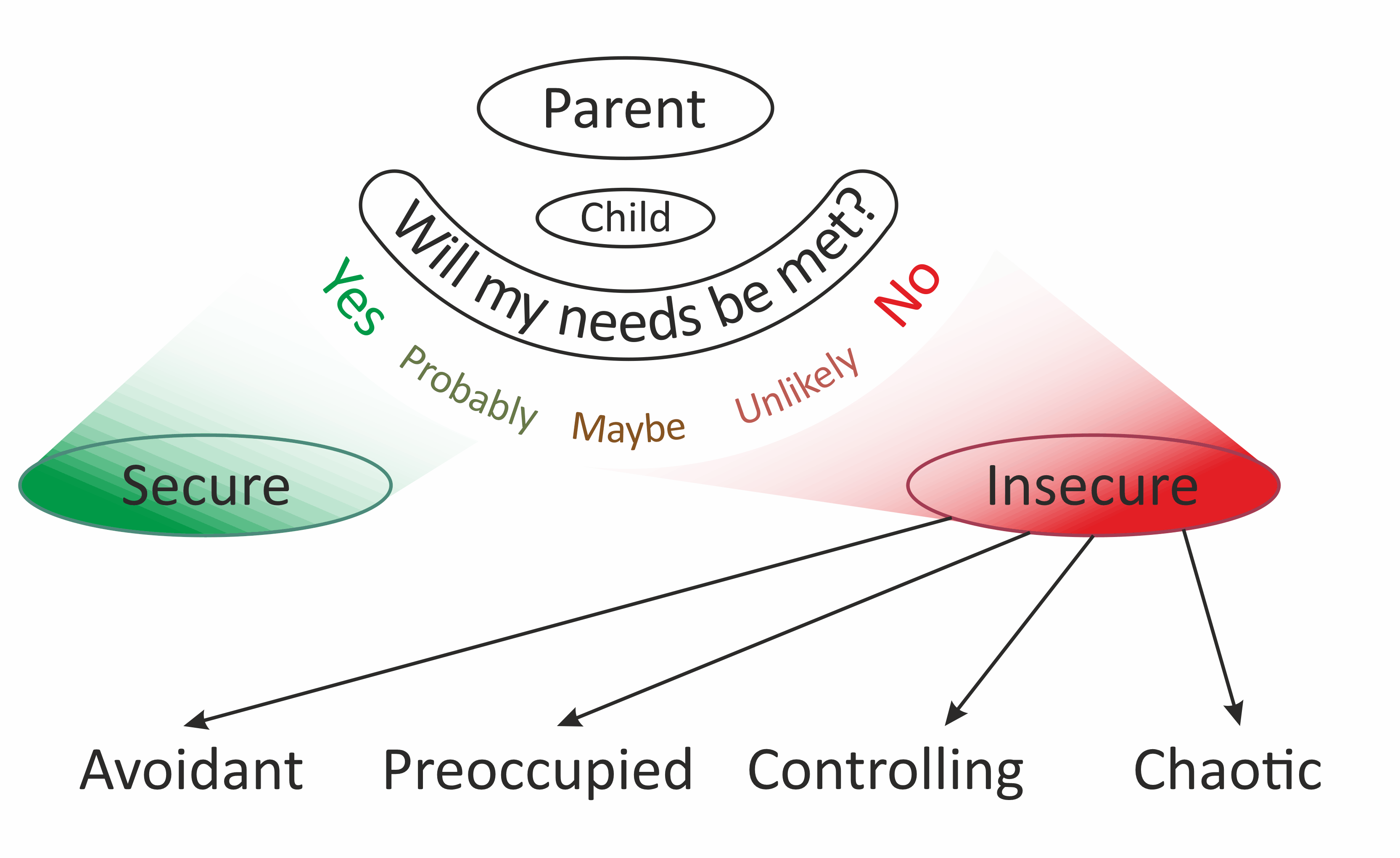

Attachment Theory is a way of looking at how and why we modify our way of being in the world in response to the kind of caregiving we received in childhood. We all have a unique innate wishlist for the parenting style we would like – Al Pesso called this our genetic template of expectation. This is not always a conscious process but on some level we assess whether our needs are likely to be met by the caregivers we have.

Can any caregiver meet all our needs?

Short answer: No, but all we need is good enough parents and it seems that good attunement to our needs about 25% of the time is enough. So the system is fairly robust and some misattunement (rupture of the relationship) followed by making good (repair) seems to be beneficial too. Nevertheless only about half of us emerge from childhood securely attached.

What is Secure Attachment?

If our childhood assessment is that most of the time our needs will be met by loving and caring parents we relax into the idea that we are OK and the world is a generally safe place within which to have, and express our needs.

And if not?

If we conclude that our needs will not be reliably met, we adapt our way of being in the world in order to survive. This is in some relation to the severity of the situation, what attachment style our caregivers have’ and some aspect of our personality. This way of being in the world is called an insecure attachment style. The term is really a technical psychological description but sadly the word has entered common usage as a disparaging term.

Everything is OK, until it’s not.

It’s fine to have an insecure attachment style – half of us do. Nevertheless, it can have implications for the way we form and conduct our adult relationships, so it’s a good idea to be aware of our attachment style. There a number of common styles which I describe below.

Avoidant

One way to adapt to the conclusion that our needs will not be freely and reliably met is to switch off our internal connection to our needs. That way we become less aware of our needs with the result that the pain and frustration of them not being met is reduced. This style is called Avoidant. Our needs don’t actually go away, but we are less aware of them. Later in life we might not feel a strong need for relationships. Stan Tatkin refers to people with this style as ‘Islands’. Perfectly happy alone on their island and willing to receive visitors who don’t overstay their welcome.

Preoccupied

Another adaptation is to be very aware of our needs and always be checking that others know that we are here and keen for our needs to be met. In common parlance we might say that such people seem needy, and the psychotherapeutic term is Preoccupied. Stan Tatkin refers to people with this style as waves because they often swamp their partner then retreat in fear that they might be rejected.

Controlling

Sometimes there are people who make sure their needs will be met by requiring it to be so. This is nevertheless coming from a place of fear that they won’t be met, so it’s still an insecure style. We often call such people controlling.

Chaotic

In some cases the childhood environment was unstable and confusing, maybe dangerous. This can lead to an attachment style that swings erratically between the various types. This might be called a Chaotic attachment style.

What style are you?

You might recognise aspects of yourself in some or all of these descriptions, and we all have the capacity to embody various styles, including secure. Perhaps the main style is the one we go to when we are under stress. We often experience stress in relationships when they are not going so well and this is how attachment style can have implications. We also grow and develop at different rates within relationships which can throw any ‘style disparities’ into view.

Can you learn a secure attachment style?

One of the possibilities in therapy is to become aware of our attachment style and learn to become ‘secure’.